One of the key aspects of Blockchain / Distributed Ledger (DL) Technology is the ability to merge public key authentication of information with a resilient, distributed database. In this piece, which outlines an application Eris is building, I talk about this idea in greater detail using publicly available data from the Legal Entity Identifier (LEI) initiative.

There is no shortage of news, blog posts, and whitepapers foreshadowing the disruption of entire industries by blockchains and describing a myriad of potential use cases that will run more efficiently on a decentralized architecture. What is striking is that almost all prominently discussed topics focus on processes and scenarios with a fair amount of complexity and/or attempt to replace very established procedures. At first, this seems logical since the potential for efficiency gains usually increases with the complexity of the use case, but it seems we’re rushing too far ahead and have forgotten about one fundamental formula that has always proven helpful when venturing into new territory:

Start small, learn what works and what doesn't, and build up from there

We at Eris Industries are very much about “less talking, more doing” as subscribers to our blogs and Twitter account can surely attest. So, in this article I would like to hone in on a ‘real world’ use case that exemplifies what can be done with blockchains today.

It is very understandable that people may feel they should wait and gain more experience and confidence with this fairly new technology before investing much effort into it. Even when investments (usually in the form of POCs or in-house / consortia experimentation) are made, many might hesitate to build and deploy real solutions on shared ledgers until potentially a ‘winner’ emerges, be that a blockchain design or a common industry platform. However, I would like to show here that the technological components are mature enough, especially in Open Source, to extract value and start building now.

“Transformational ROI from blockchain for corporates will take a good number of years. Smaller bits of ROI can be achieved tomorrow if you have the right buy in and strategy and partners.”

Simon Taylor, Nov.

When carefully selecting use cases, opportunity opens up to implement something beyond POCs that contributes to the learning experience at the same time.

“Blockchains are a new type of hammer that can hit new nails. We don’t fully understand what the new nails look like yet, so let’s keep hitting old nails until we understand the new hammer. So it makes sense to apply this technology to well understood problems, even if they can be solved using existing technology.”

Antony Lewis, April

Blockchains by design come with a set of features that is desirable in most (enterprise) applications, even if it’s merely to reduce operational expenses for hosting, failover, or disaster recovery. The availability of blockchain platforms and toolkits further reduces costs of building custom solutions.

So, shall we dive into a discovery and selection process of what we should build?

First, in order to increase the chances of arriving at a level of production-readiness let’s avoid any of the big unresolved challenges of blockchains/DLT, namely:

- High Transaction Volume

- Confidential Transactions

- End-User Identity

Second, the number of participants profiting from a blockchain solution should be as high as possible, after all it’s a shared ledger. As detailed by Gideon Greenspan in articles from October and November of last year, blockchain technology as a shared writable data store has private as well as public utility, but the public domain should be considered as a category that trumps most other checkpoints.

Third, to be mindful of the start small, build up mantra it should be our goal to identify a simple use case upon which more complex scenarios can be built. This means we’re looking for low complexity in the business processes at a network level, i.e. a small number of interactions between disparate entities in a low-trust environment, yet delivering value through the shared content. Two pillars underpinning many higher level business processes are Master Data Management and Reference Data Management.

Without further ado … meet the candidate to be ‘ledgerized’.

The Legal Entity Identifier (LEI)

“LEI data is freely available, easy to access, without restrictions on redistribution or licensing. […] Future phases will require a new ‘utility strength’ global infrastructure, which will have similar robustness, reliability, and business continuity capabilities as other financial market infrastructures, such as securities settlement systems and trade repositories.”

From the original scope plan

The LEI initiative emerged out of a request by the G20 to the FSB in to establish a globally unique identifier for legal entities, primarily to increase transparency of their involvement in global financial transactions (something that could’ve doubtlessly been of value when sifting through the mess of a global meltdown of the financial system, but let’s not get into that …).

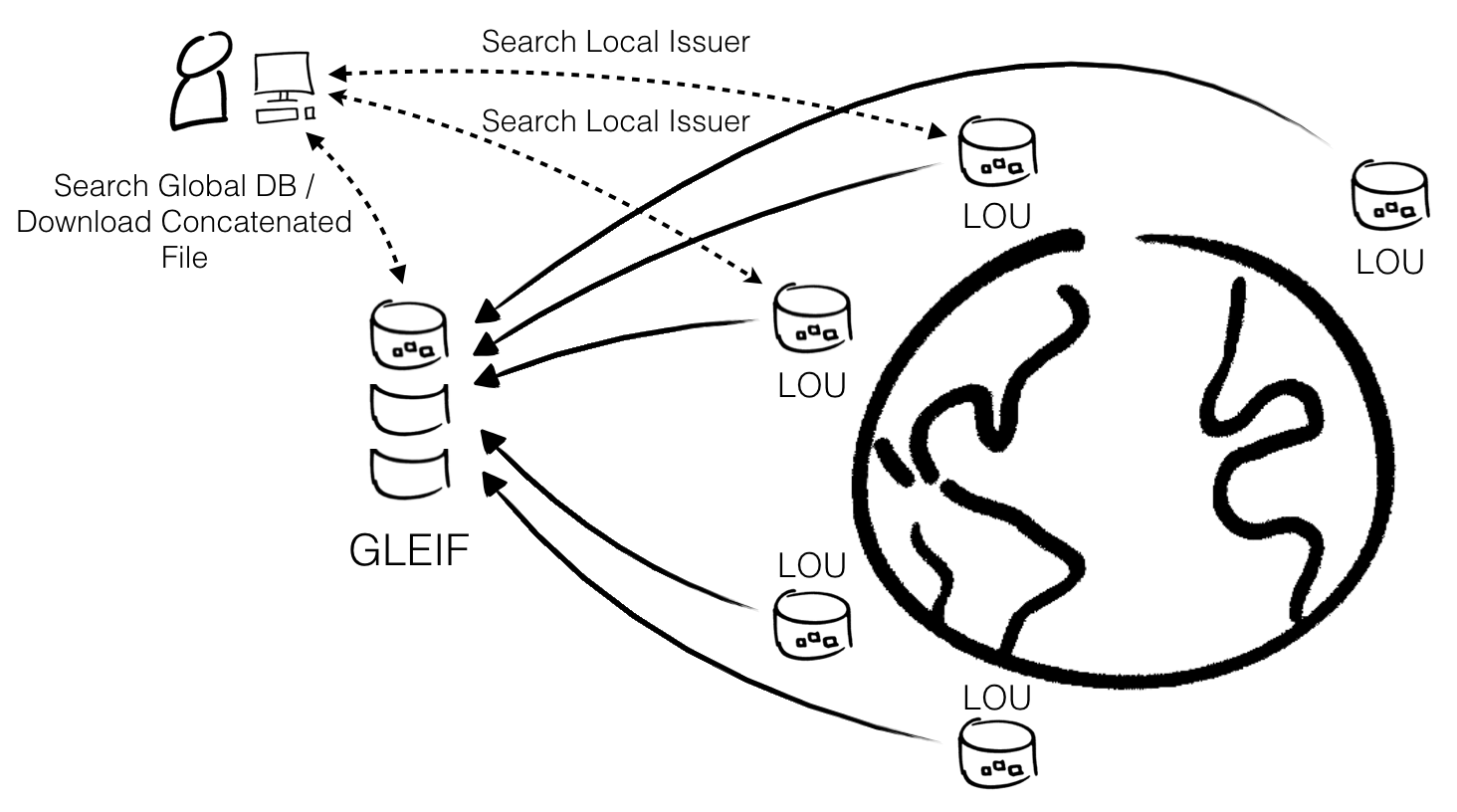

The LEI system as it exists today operates in three tiers:

- The Legal Entity Identifier Regulatory Oversight Committee (LEI ROC), comprised of more than 50 regulatory institutions worldwide and a variety of public sector stakeholders, monitors the system.

- The Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation (GLEIF) is in charge of governance.

- Local Operating Units (LOUs) are accredited agencies that function as the beachhead in local jurisdictions / countries to render services around the LEI, e.g. issuing LEIs to local businesses.

Briefly a few facts about the LEI system:

- It is an LOU’s primary responsibility to certify that the information about a company (legal name, registered address, headquarters address, entity status, etc.) is valid and current. To do so it sometimes relies on services of third-party companies like Avox (a subsidiary of DTCC).

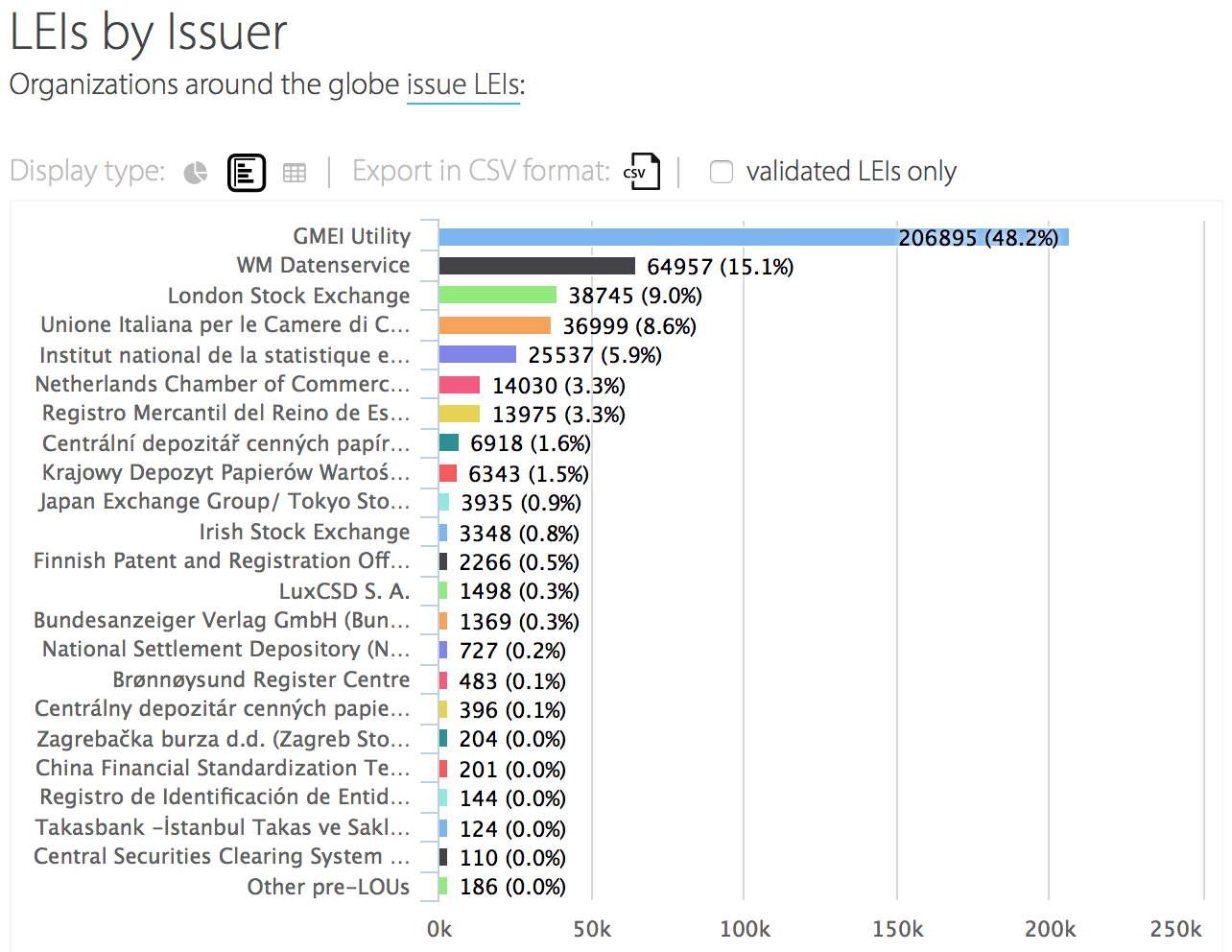

- The GMEI Utility operated by the DTCC in collaboration with SWIFT is by far the largest such LOU in terms of issued LEIs (see diagram below).

- An LEI record possesses a lifecycle that goes through different state changes (active|not_active, current|not_current, etc.) and also expires if not renewed. This lifecycle is supported by a simple business process / workflow.

- LOUs, third-party verifiers, and legal entities themselves participate in this workflow. For example, a company can register, update, or dispute their own data (which still requires verification or approval by the LOU) or request the LOU to do so on their behalf.

- The LEI format is based on ISO Standard 17442 and follows Financial Stability Board (FSB) specifications. The LEI consists of a 20-digit alphanumeric code.

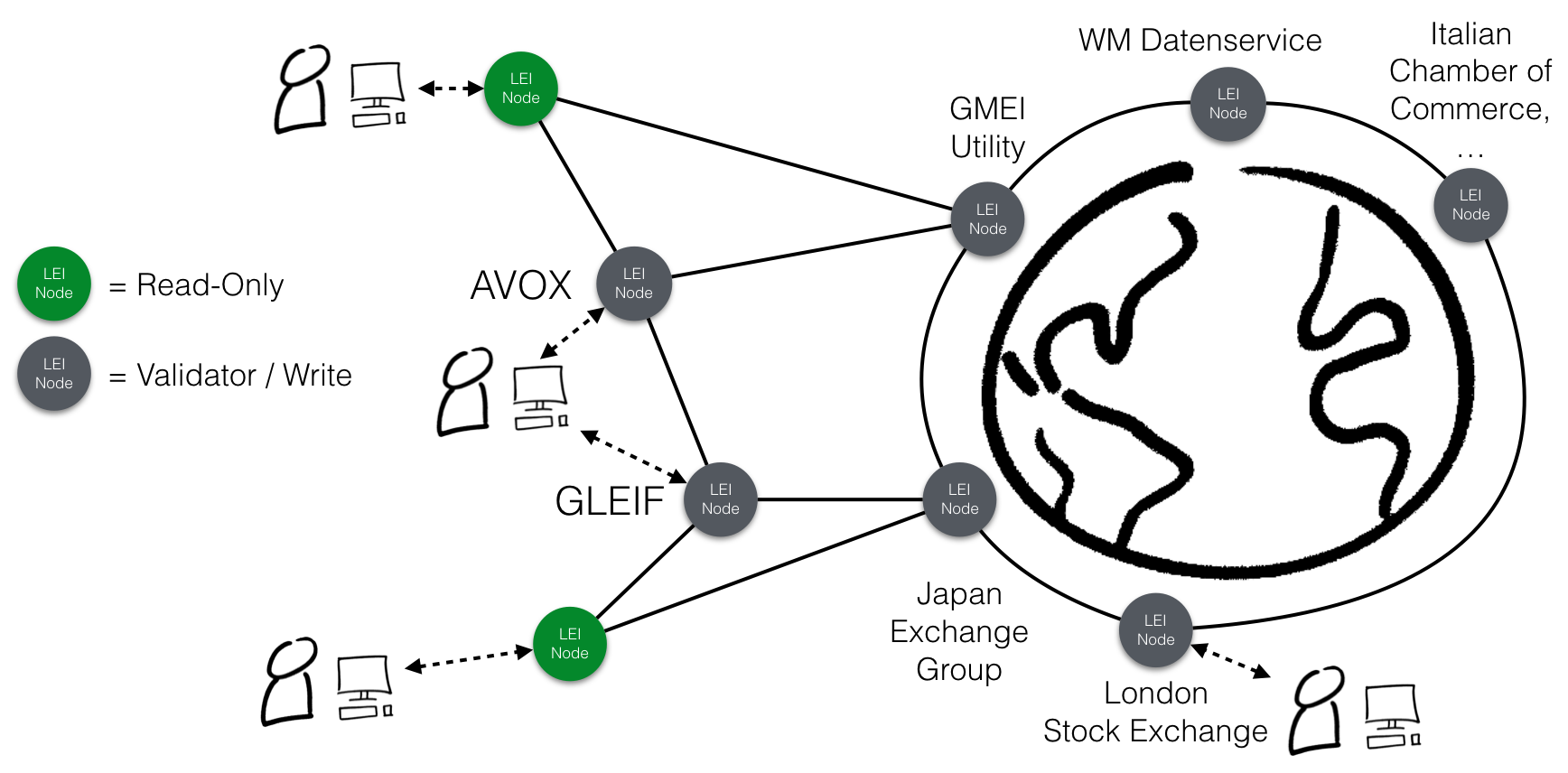

Each of the certified issuance agencies (LOUs) in the above list owns, runs, and maintains its own infrastructure (servers, web application, and centralized database) to offer LEI issuance and search capabilities. The delta of changes at an individual local agency is uploaded and consolidated into the global “golden copy” that is managed by the GLEIF as depicted in the following diagram.

The cost of running and maintaining the LEI infrastructure is probably not very high compared to solutions with higher transactional volume. The individual LOUs cover parts of their costs by charging fees for registration and other maintenance transactions. As of this writing the combined fees for registering a new LEI are approximately $220 dollars.

The LEI system went live, the same year blockchain as a general concept separated from Bitcoin and entered the spotlight. It is an intriguing thought experiment - now that the capabilities of blockchains are more widely discussed - what this system would look like had it been implemented on a distributed, participatory architecture.

So, let’s look at this scenario in more detail and examine the stages of implementing the LEI system as a global shared ledger.

The LEI Global Ledger

Since its early days, Eris Industries has been advocating the utility of a blockchain as a data management tool with unique properties: It stores both its state & transition logic (simply put, it houses the data records including the rules that govern them, i.e. authority to access and change as well as the legality of changes). Furthermore, a blockchain distinguishes itself from previously known distributed database approaches by not having a central owner or administrator.

A blockchain therefore allows us to store and share a single version of the ‘truth’ about the state of all LEI data as well as encode and enforce the validity of changes to this data via smart contract logic. All while the infrastructure is jointly operated by its network participants.

Permissioned blockchains and ownership

At this point it is important to take a detour and explain why this particular use case requires what is known as a permissioned blockchain which necessarily introduces a level of control and ownership.

Control is expressed in the permissioning layer which authorizes peers to connect to the network in different roles. For example, the group of peers responsible for validating transactions and coming to consensus on the global state of the system should be configurable as a white list of known actors. The same applies to the peers specifically allowed to commit changes to the ledger; every node on the network with ‘write access’ to the ledger needs to be identifiable and associated with a known participant, for example, a local issuing agency (LOU). However, due to the public nature of the data, read access should not be restricted at all and anyone should be allowed to connect a ‘read-only’ peer. This approach of permissioned 'write' and public 'read' is sometimes also referred to as hybrid blockchain.

Ownership needs to be established in the form of a trusted entity to:

a) guarantee the availability of the network, e.g. by running the minimum number of nodes required to keep the system available

b) function as the trusted custodian of the smart contract logic (including versioning and updates) and provide legal liability

It is likely that many shared ledger solutions, especially the ones touching upon the public domain, are going to require a certain form of centralized control to maintain and version the ledger software itself as well as the smart contract code running on it. For different use cases one can imagine non-profit or publicly funded organizations, governments, municipalities, etc. to assume such responsibilities in the future.

In the financial realm there already are a number of organizations that are well positioned to fulfill the role of becoming future shepherds of decentralized, distributed infrastructure and the programs running on this infrastructure: FSB, SIFMA, ISDA, DTCC, SWIFT … to name a few.

Other sectors, such as healthcare, have similar umbrella organizations and for many other use cases that are going to be identified as potential distributed, shared ledger applications the local or federal government might be the default candidate to play the role of the ‘trusted custodian’. Or will we create DAOs for this? If Bitcoin has taught us one thing: Creating a blockchain protocol appears to be easier than governing it.

In his presentation William Mougayar stated:

“Blockchain and old constructs, such as clearing houses and private exchange networks (SWIFT, CCP, FIX, DTCC) are like oil and water: they will not mix well because one is based on centrally trusted intermediaries, and the other is based on ‘no’ intermediaries and peer-to-peer trust.”

With reference to the points made above, I respectfully beg to differ and recent publications appear to confirm that organizations like the DTCC are beginning to open up to the exact same ideas outlined in this article:

“DTCC’s viewpoint is that basic industry master data is an ideal candidate for improvement using decentralized consensus, rule standardization and auditable change history. This information is used by the entire industry by definition, and the lack of consistency and quality is a recurrent industry problem. Further, this could be constructed in such a manner that multiple firms can be authorized as data submitters, there can be many data validators and the majority of users will be data consumers.”

DTCC’s ‘Embracing Disruption’, Jan.

Now, let’s get back to the LEI ledger implementation …

Architecture Overview

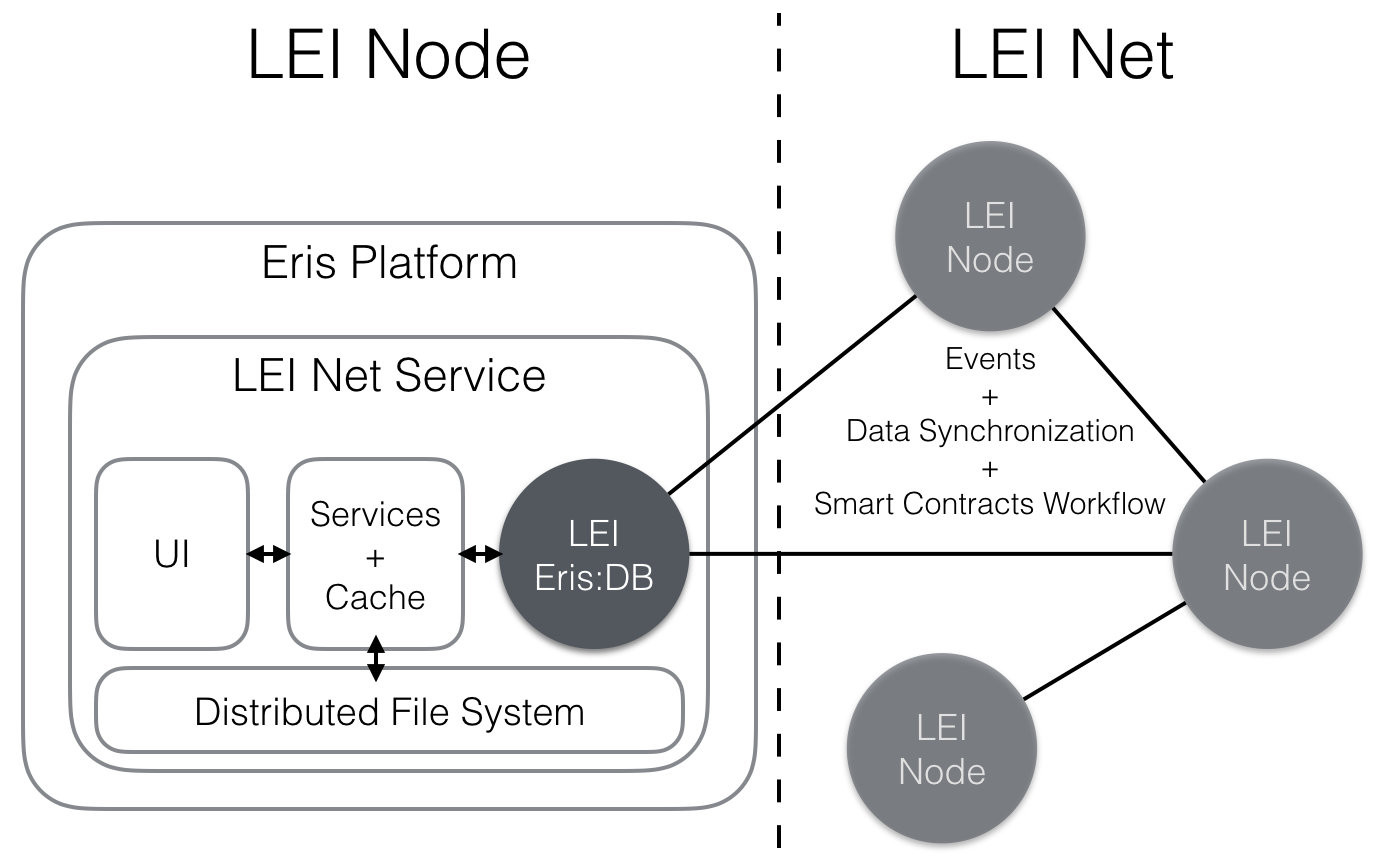

The diagram below outlines the components of a single peer node of such a network built using the Eris Platform.

The Eris Platform is a free and open source (FOSS) platform that facilitates building, testing, and running smart contract applications. It supports the notion of a service as a single module that can be started, stopped, and monitored easily. The LEI application and the parts comprising a peer node participating in the LEI Global Ledger network are wrapped inside such a service.

Eris:DB is the permissioned blockchain implementation (see Permissioned Blockchains above) based on the Ethereum Virtual Machine for smart contract execution and Tendermint for efficient, non-forking PBFT consensus. The application consists of a number of service modules facilitating the interaction with the LEI blockchain, i.e. providing access to data on the chain as well as allowing the application to react to events in the network. Furthermore, a distributed data store is used to redundantly store the entire legal entity record. Note that the smart contract only contains the LEI itself, the data fields used in the smart contract logic, as well as the reference hash to the stored record. All legal entity data is also kept in a traditional database that functions as a cache and is kept in sync with the state registered in the blockchain. This supports the ability to index and search the content.

Essentially, this application (in its intended final state) would behave the same way and provide the same services as the GLEIF’s global search capacity combined with an LOU’s registration and maintenance capability (if the peer owner has been permissioned with a write access role!), but running distributed on all nodes of the network instead of a centralized server. … Good bye backups, fail-over, and disaster recovery! You’re welcome DevOps!

The following sections outline the stages that can enhance and eventually transform the existing LEI system to a distributed ledger. Stages 1-3 are designed to be completely non-disruptive to the current LEI system. During these stages the LEI Global Ledger is operated in parallel to the existing infrastructure with increasing effort and inclusion of participants. This allows interested parties to share in the experience of a live blockchain application with real data; all with a minimal investment and no risk. Stage 4 (and beyond) requires definite buy-in and sponsorship by the stakeholders of the LEI eco-system due to the declared intention to eventually replace the current centralized infrastructure with a distributed, blockchain-based one.

Stage 1

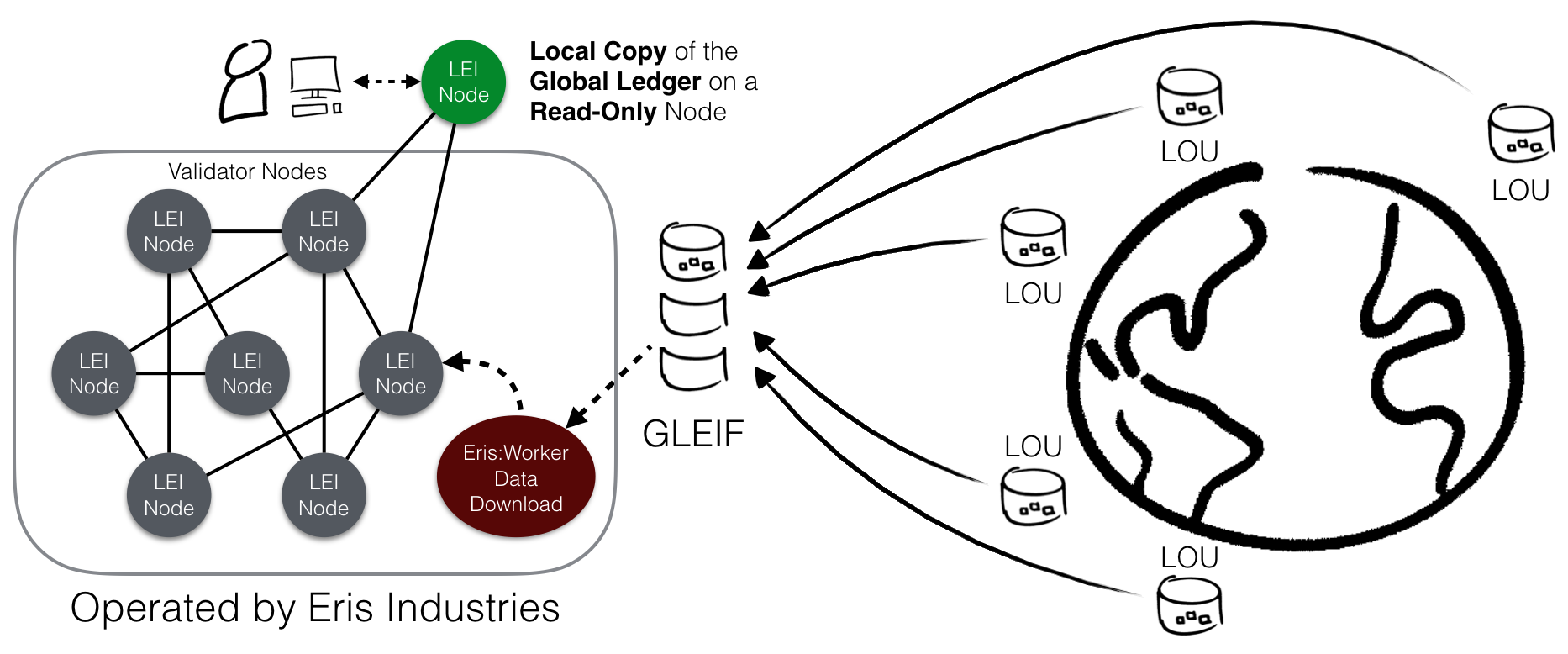

The global LEI data is freely available for download and an update is published daily. In this first stage there is no buy-in or support from any participant in the existing system. Eris Industries is responsible for downloading the daily updates and cryptographically signing the transactions that push these updates into the LEI ledger.

The immediate effect for any consumer operating a ‘read-only’ peer is that access to LEI data is changed from a pull to a push mechanism.

This stage has been implemented by Eris Industries! Please see the end of the article for instructions how to participate.

Stage 2

In stage 2 an entity with authorized access to the global LEI database would assume responsibility for vouching for the data veracity by signing transactions to commit updates to the ledger. The GLEIF seems to be in a perfect position to do so. The transition to this stage is as easy as hooking up a few database triggers to capture update/insert events and forward these to the blockchain.

Stage 3

The same mechanism of hooking into a database as described in stage 2 is leveraged here, but it would be the LOUs themselves that propagate data into the blockchain and the central synchronization point at the global GLEIF database can be removed. With this stage we’re closing in on the LEI ledger allowing a near real time view of the LEI records as events get reported to the ledger much closer to their points of origin. At any time the LEI ledger would provide a more accurate view of the entire system than the daily consolidated file download can provide. A beneficial side effect of the LOUs cryptographically signing their own data commits is that they become identifiable via their signatures in the ledger’s audit trail.

Stage 4

Assuming a successful exploration and validation of the LEI ledger in stages 1-3, a blockchain-based LEI system might be deemed feasible and worthwhile considering as a full replacement of the centralized infrastructure.

However, before the latter can simply be switched off, there is some effort involved to implement and test the integration points to any centralized systems that would remain in place and now need to interact with the ledger’s API.

At the end of stage 4, all core participants of the LEI lifecycle would be fully onboarded to participate in the smart-contract-backed workflow purely through signed transactions. Known participants include all LOUs and, if applicable, third-party data verification services.

Beyond Stage 4

Potential future enhancements to the system beyond stage 4 include:

- Legal entities participating directly in the workflow, verifying the correctness and signing off on their own data for renewal. This would require a more common and pervasive use of Public Key Infrastructure (PKI). It is not very difficult to foresee that a company having gone through a verification process to prove its identity might want to register more than the legal address in the LEI ledger, e.g. their public keys. Quite sophisticated B2B processes can be built from there!

- Another thought experiment involves the possibility to introduce free market economic principles into the system and open up the fee collection to competition. A legal entity could simply post a registration request with a certain fee associated as a reward that can be claimed by a third party for rendering services successfully.

This last one is admittedly a bit far-fetched and has legal implications that cannot easily be solved with a smart contract alone (yet), so let’s leave it at this.

Conclusion

Let’s be realistic … the existing LEI system works sufficiently well, so why would you even want to attempt to replace it? “Because we can” is not an answer that will convince any of the stakeholders!

My main motivation for writing this post was to get people that are interested in blockchains, smart contracts, and distributed applications thinking. To show what’s possible and that we don’t have to wait years to build something meaningful, something that provides value to a large audience.

I hope I was able to demonstrate the viability of transforming an existing system like the LEI from a number of loosely joined, centralized data islands to a shared distributed ledger / smart contract application. All with very minimal investment and low to no risk in the early stages. A chance for people to experience a real blockchain application first-hand.

You might be thinking that there is a risk of “blockchain (or vendor) lock-in”. However, running the proposed solution side-by-side with the existing LEI system eliminates any risk (for the time being) of betting on the wrong blockchain. Even if at a later time a different blockchain implementation becomes more suitable, one of the benefits of this design is that control is introduced via trusted custodians who have the authority to perform a data migration by recommitting all historical transactions to a new ledger, albeit the original transaction timestamps would likely get replaced. Downstream systems would experience minimal to no disruption as long as a standardized data format is adhered to (e.g. the LEI system defines an XML Schema specification).

If the benefits of maintaining a globally unique registry, like the LEI, on a shared distributed ledger as a single source of truth can be proven and established, then it is not difficult to repeat the same for data with similar characteristics, e.g. the Unique Product Identifier (UPI). The success of such initiatives would unlock more sophisticated use cases that require a deeper involvement of existing market participants: how about Corporate Actions reporting and validation on a shared ledger?

Verifiable public data in a trusted, distributed, participatory infrastructure can foster open innovation and unlock future use cases. Replacing existing (centrally run and controlled) services with distributed, community-supported ones would allow public, private, and especially governmental institutions to “outsorce” IT infrastructure to their own communities or citizens.

“Where individuals, businesses and governments are constantly locked in a battle against bugs, fraud and malicious actors, blockchains propose an alternative. […] The paradigm shift blockchains represent can offer true data integrity, advanced digital identity systems and a new way for business to offer transparency for audit alongside access for third parties.”

Ben Rossi, Dec.

Remember: Eris Industries already built the LEI Global Ledger as depicted in the Stage 1 diagram and we’re intending to voluntarily run this network for the time being, so that others get a chance to experience what a distributed, smart-contract-enabled solution feels like.

If you’re interested in this use case and its implementation, e.g. if you’d like to experiment with a read-only peer node or want to develop a business case out of this solution, please don’t hesitate to contact Eris Industries Please voice your opinion (good or bad) and feedback on this article by tweeting it with the hashtag #leiledger.

We are going to collect requests by interested parties and intend to make the LEI Net Service available as part of one of the next Eris platform releases.

The smart contracts controlling the LEI lifecycle and workflow can be used as the basis to implement similar data repositories. They are being made available to subscribers of the Eris Contracts Library.

Disclaimer: Diagram graphics by Timothy Morgan redistributed under CC License