1) What is the problem we are trying to solve?

Users of the modern internet have an immediate need for increased security, increased privacy, and increased efficiency of data management.

Current server-based solutions are expensive to operate and administer. As they scale, they become more expensive.

Peer-to-peer technology should enable application developers to enlist their users in scaling an application, by lending use of their hard drive space and their processing power. By asking users to participate in the management and scaling of an application, a software design paradigm we refer to as participatory architecture, we hope to lower the barrier to entry for the production, distribution and maintenance of interactive applications by application developers that can perform the same functions of modern web applications.

At Eris Industries, we build tools to utilise and leverage this technology. We have built:

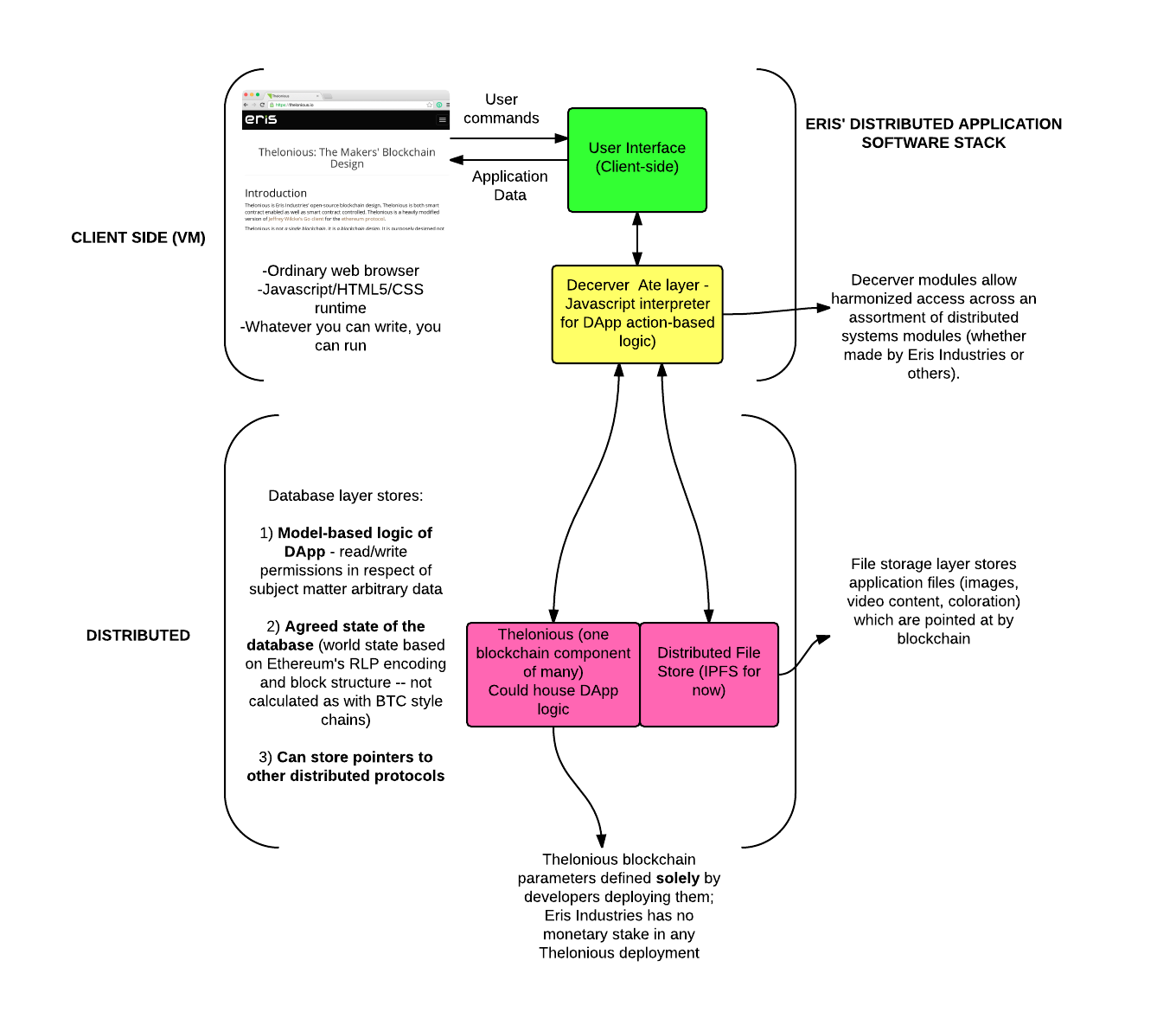

- a decentralised application server, called the Decerver, which allows blockchain databases to refer to and interact with other distributed protocols; and

- a blockchain design called Thelonious which can be used to hold, secure, and distribute the logic of such applications.

2) Why is this a problem?

Users of interactive applications – financial, social networking, communications, or otherwise – expect that interactive applications (which, today, are mostly web-based) are free. However, hosting providers who lend the infrastructure and servers for distributing and operating those same interactive applications do not share the users’ expectations.

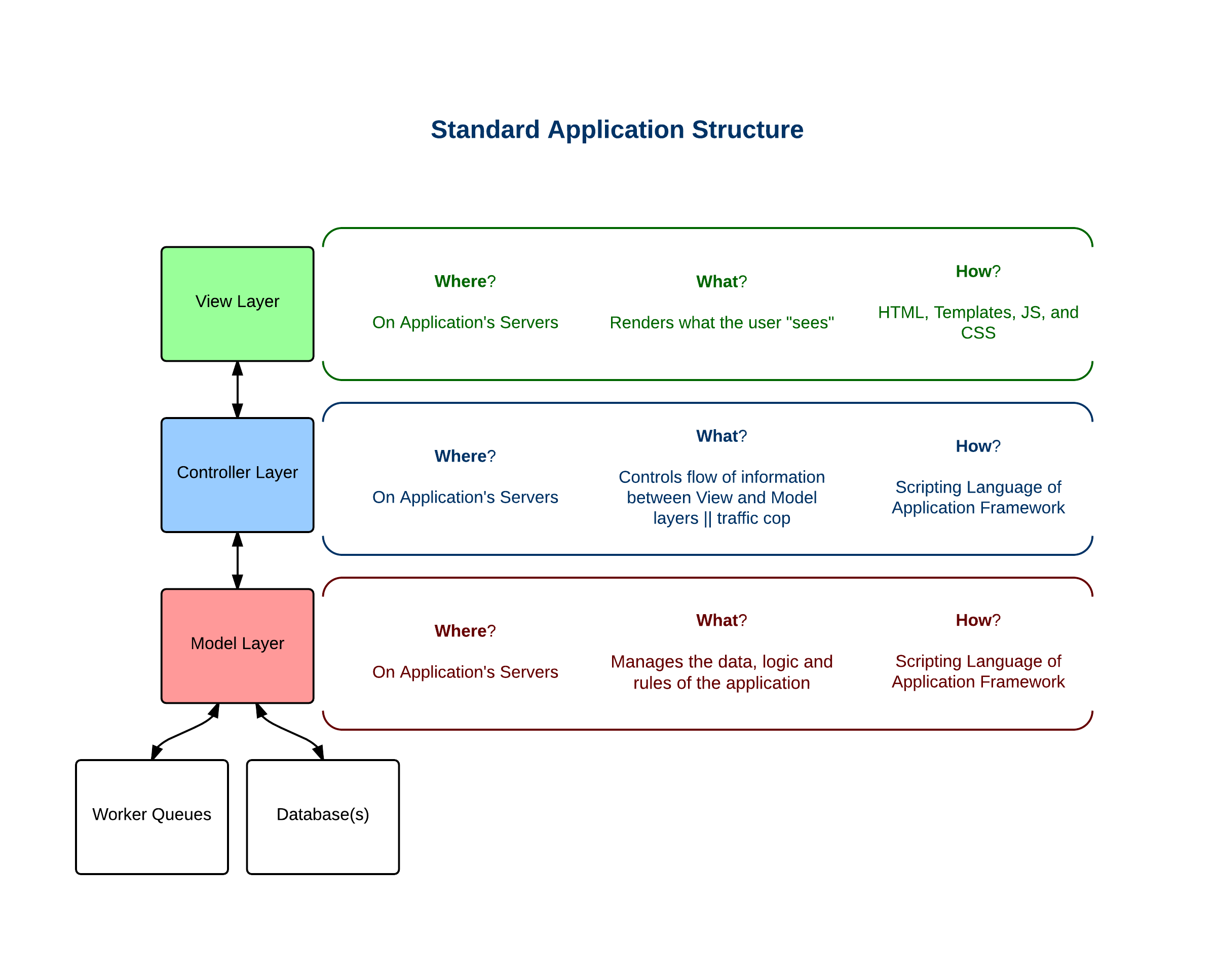

Structurally, this kind of application architecture might be represented like this:

As we can see, the sole responsibility for delivering applications structured in this way is on the application developer. This is expensive, and leaves application developers with the challenge of managing distribution and operational costs (predominantly in the form of servers) for an application which is free to its users.

Distributed computing technology, including blockchain technology, enables developers, rather than spending money on server clusters, to enlist their users to assist in scaling the application. The basic idea is to build an application which may or may not be financially free to use, but where users provide usage of

- their hard drives, to assist in the distribution of the application; and/or

- their processors, to manage and secure it.

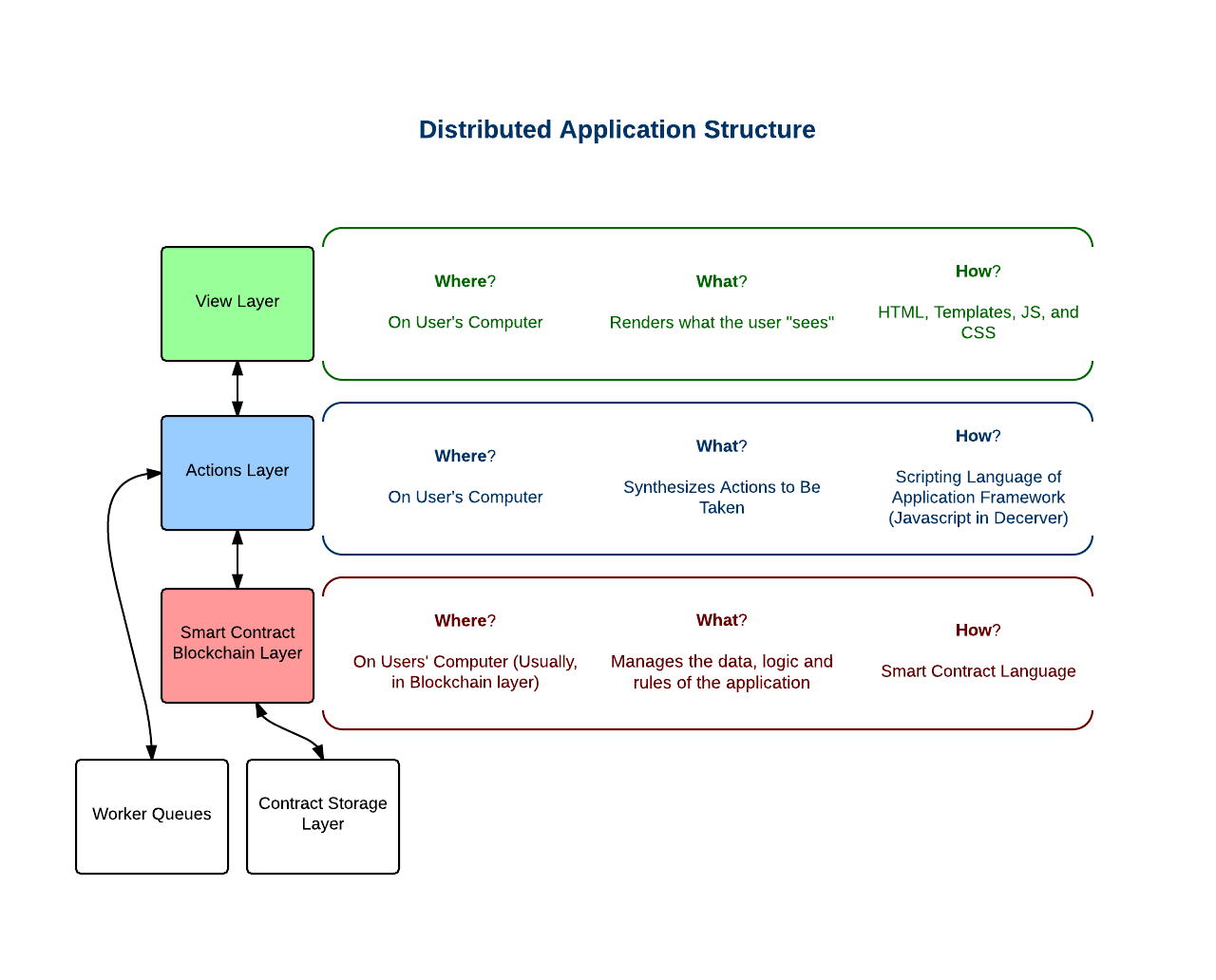

Structurally, this kind of application architecture might be represented like this:

3) We want to use blockchains as part of a new peer-to-peer design paradigm for interactive applications

Is it realistic to expect that users would be allowed to participate in the distribution and operation of an application in this way? Sure thing. Spotify has found great success using this paradigm - a paradigm we call participatory architecture.

Spotify, for instance, initially allowed users to cache files locally, and then used a proprietary technology very similar to BitTorrent’s peer-to-peer file sharing protocol to enlist the assistance of users in distributing the gargantuan quantities of content available within the application. Even though Spotify is currently moving away from a peer-to-peer paradigm, it is unavoidable that when revenues of that application were lower, the peer-to-peer technology greatly reduced costs over the course of the application’s development toward a mature platform with stable, sustainable revenue.

The core hypothesis of participatory architecture is that users will accept the tradeoff of participating in the scaling of an application for an increase in data ownership over data which is, fundamentally, theirs. Data which users decide to place into a distributed data store utilized by a distributed application should always be opt-in, and they should always retain control over that data using public-private key encryption.

Desigining software using a participatory architecture paradigm, developers are able to focus on providing users with pure utility from the application and control over their data rather than attempting to leverage that data for the developers’ sole benefit. Blockchain architecture, such as that used by Bitcoin, presents an intriguing possibility for making this architecture accessible and customisable for a wide range of applications.

4) Eris is the technology of Bitcoin – only better, and built for any arbitrary data.

Today, blockchain databases are most often seen in internet applications known as cryptocurrencies. Cryptocurrencies, the most famous of which is the well-known Bitcoin, are interactive software applications where the users, instead of a central authority, assume responsibility for the application’s maintenance, security, and improvement.

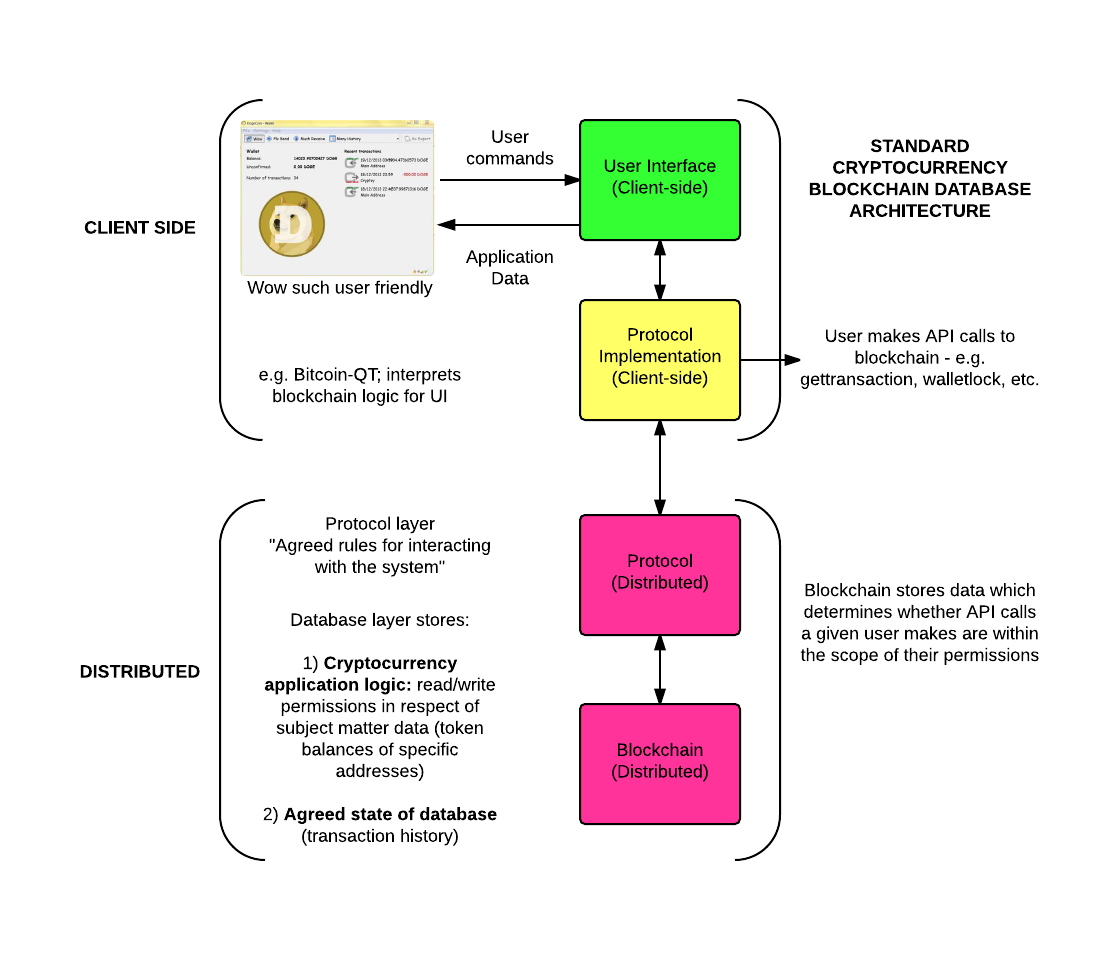

As described by Simon de la Rouviere, a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin consists of the following components:

a) A distributed blockchain database, which holds the logic of the implementation. By “logic” we mean the rules on which the users interact with each other. With a standard cryptocurrency, users have two basic permissions:

- read; and

- write.

The read permission is (in most cases) universal. Write permissions are granted to a user in respect of the one datum a cryptocurrency blockchain is designed to address: a token balance of a particular address. If a user with the requisite keypair has a token balance, submitting an API call to a blockchain database to spend that balance or a part thereof will result in the blockchain amending itself (other nodes will validate/confirm the transaction). If the user has a balance of zero (or a balance smaller than the transaction in question), the blockchain will not allow that user to write the new transaction into the database (as other nodes will not confirm the transaction as valid).

b) a protocol, which is “the agreed upon ‘language’ by the participants in a specific network to be able to work with the blockchain and its peers;”

c) a protocol implementation (e.g. Bitcoin-QT, BTCD); and

d) a user interface through which the user and the database interact (the wallet application).

We would diagramatically represent the relationship between these components as follows:

5) Enter Ethereum.

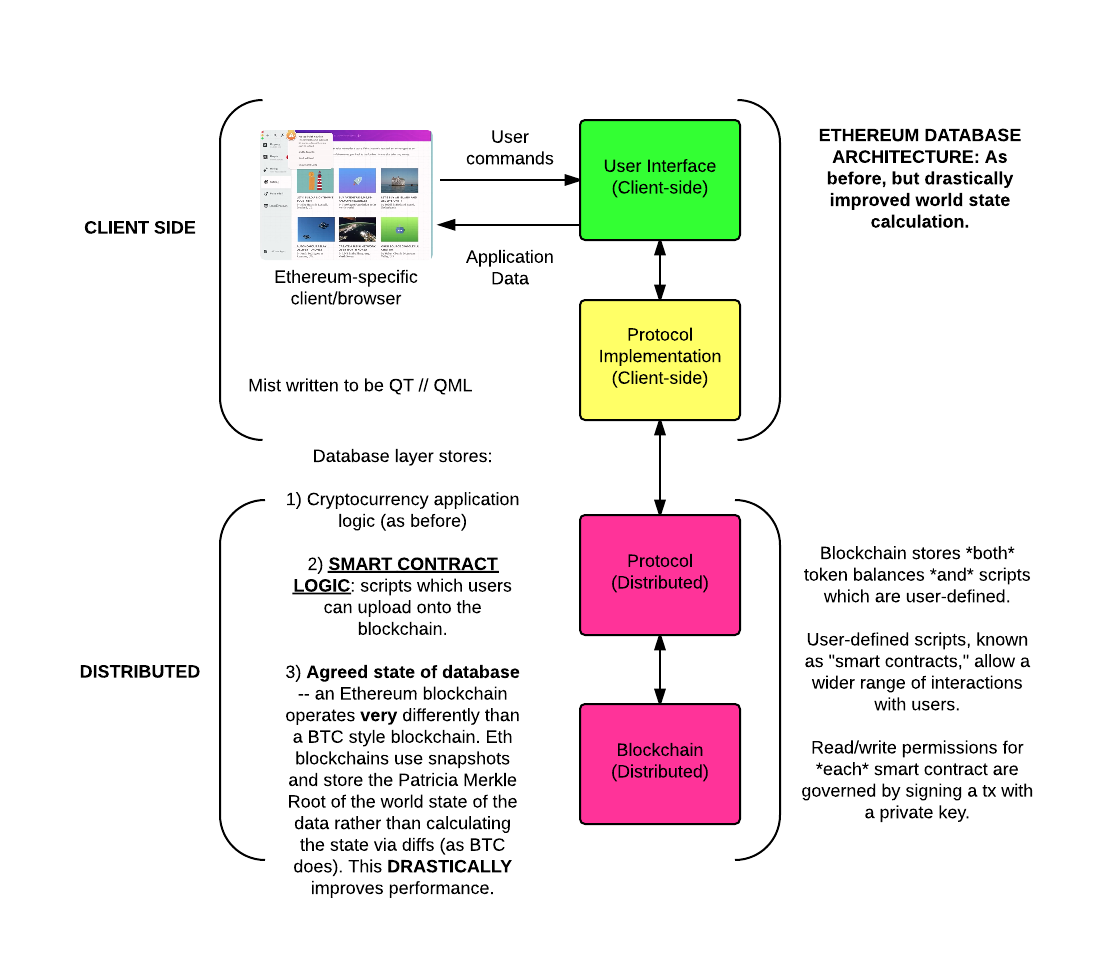

The Ethereum cryptocurrency project has a similar structure. However, it adds one function that most other cryptocurrencies do not: the write permission of any user is extended such that a user can, if they wish, upload a script onto the blockchain, which is utterly arbitrary data, that will do whatever they want it to do.

These scripts are, for lack of a better term, known as “smart contracts.” As Casey says, “they are not particularly smart nor are they contracts.” What they do is allow the person creating the script to specify

- what data the script is meant to deal with; and

- which users have read/write permissions in respect of that data.

A visual summary of how this differs, following previous examples, is as follows:

One example of a “smart contract” that one might run in Ethereum is a ledger for a sports betting pool between a small number of friends in disparate locations. If, say, five people want to keep track of their wagers in a trustless fashion, they could write a script which is designed to do so on Ethereum and amend the smart contract to reflect and/or record the respective balances.

This script is not accessible through tokens, but is accessible through write permissions specified by the smart contract itself. If you have the relevant private key, and the smart contract says you have the requisite permissions, you can broadcast a message to that smart contract and tell that smart contract to change itself in accordance with your authority.

One point which must be noted is the salient (if detailed) difference in performance which comes from the way in which Ethereum-derived blockchains differ from Bitcoin-derived (transactional) blockchains. In transactional blockchains, with bitcoin as the obvious example, the current world state of the entire data is calculated from the original time (genesis block) to the current time using the differences which are certified in each block. This slows performance greatly and is part of why some argue that blockchains make awful databases.

However, in Ethereum-derived blockchains data is stored using a much more efficient patricia merkle tree and is referenced using the specific contract address and storage slot of a particular contract. This storage paradigm greatly improves performance for both storage and lookup of data values as compared to transactional blockchains. While still moderately slower than a traditional database when writing to the data store, data lookup can be crafted in a manner which rivals traditional databases. How these data lookups are structured will depend on how the contracts store data – which we will be covering in a future post.

6) Cryptocurrencies make blockchains useful for unregulated value transfer systems. Eris is designed to make blockchains useful for everything else.

Eris takes the Ethereum concept a few steps further.

We recognised that if you can pair a blockchain with a comprehensive scripting capability, you can tell this blockchain to do whatever you want.

If you can tell a blockchain to do whatever you want, you can attempt alternative consensus arrangements - including setting those parameters to get the

- predictability,

- verifiability, and

- low-cost fault-tolerance

deploying a blockchain allows, completely free of charge (no token purchase needed), without needing to do things like mine it.

You can also write in:

- access controls,

- administrator permissions, and

- the ability to amend the logic of the application on command,

without needing to fork the chain. Usually, because a specific protocol implementation is built to link the protocol to a specific UI, if you change the protocol you need to get the users to change their clients as well. With Eris, you don’t have to, thanks to the Decerver.

At Eris Industries we see blockchains as tools, not investment products. Think MongoDB, Apache, SQL. And Blockchain. When you look at a blockchain this way, you find they are capable of not only governing cryptocurrency logic (and cryptocurrencies are applications, remember), but can govern the logic of anything else, while leveraging the distributed internet to provide most of the remaining functionality. Social networks, front-end banking platforms, version control and collaborative working - literally anything.

So the structure of our application changes again:

The end result is that you get something that looks and feels a lot like a regular web application. Except, from the application developer/administrator’s perspective, it’s a lot cheaper, because your users provide the hard drive space and processing power to run these applications - not a server mainframe.

User participation in the management of the application means that they get increased security and that applications can be designed that incentivise developers to not intrude on user privacy.

We’ll say it again: Blockchains are tools, not investment products. At Eris Industries, we build the tools to make them better, and more useful for, developers and businesspeople just like you.